As fatigue can affect stability and visual acuity in surgeons, it is essential to minimise it. Surgical Headlights are often a significant cause of fatigue, as they can lead to musculoskeletal strain, eye strain, and visual fatigue¹. This is why design plays a crucial role in helping maintain continuity and reducing strain.

Reducing fatigue in surgeons yields multiple benefits, including improved cognitive performance and lessening long-term musculoskeletal disorders². Studies show that spine, neck and shoulder problems are common amongst surgeons, which can be minimised by better ergonomics and improved headlight design³.

Weight & Weight Distribution

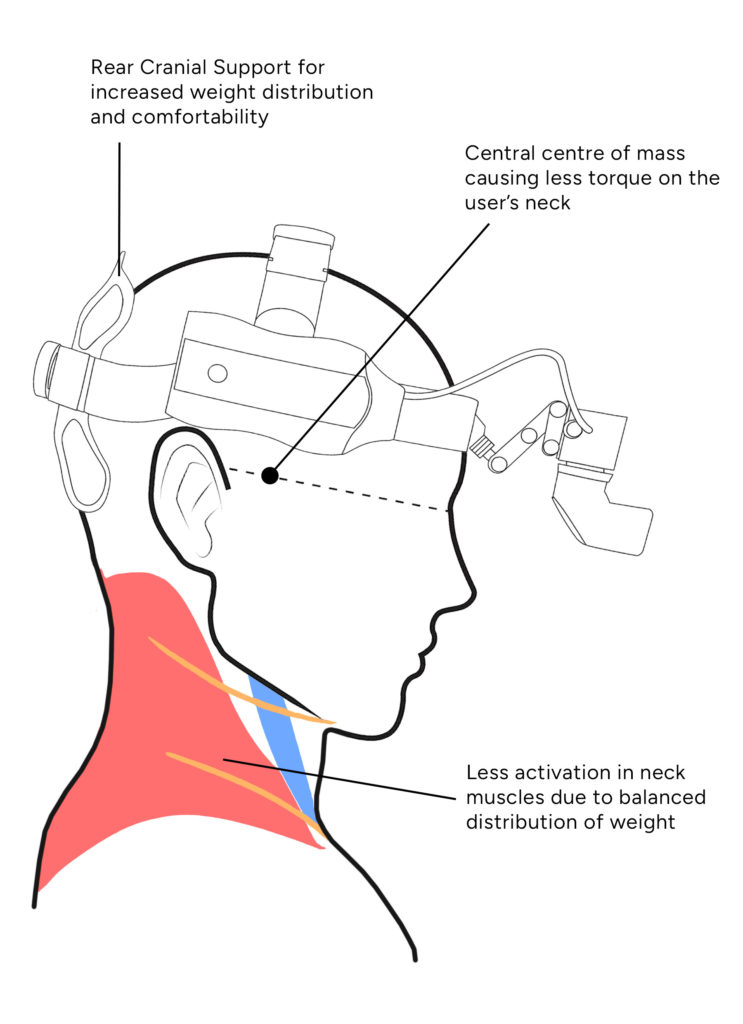

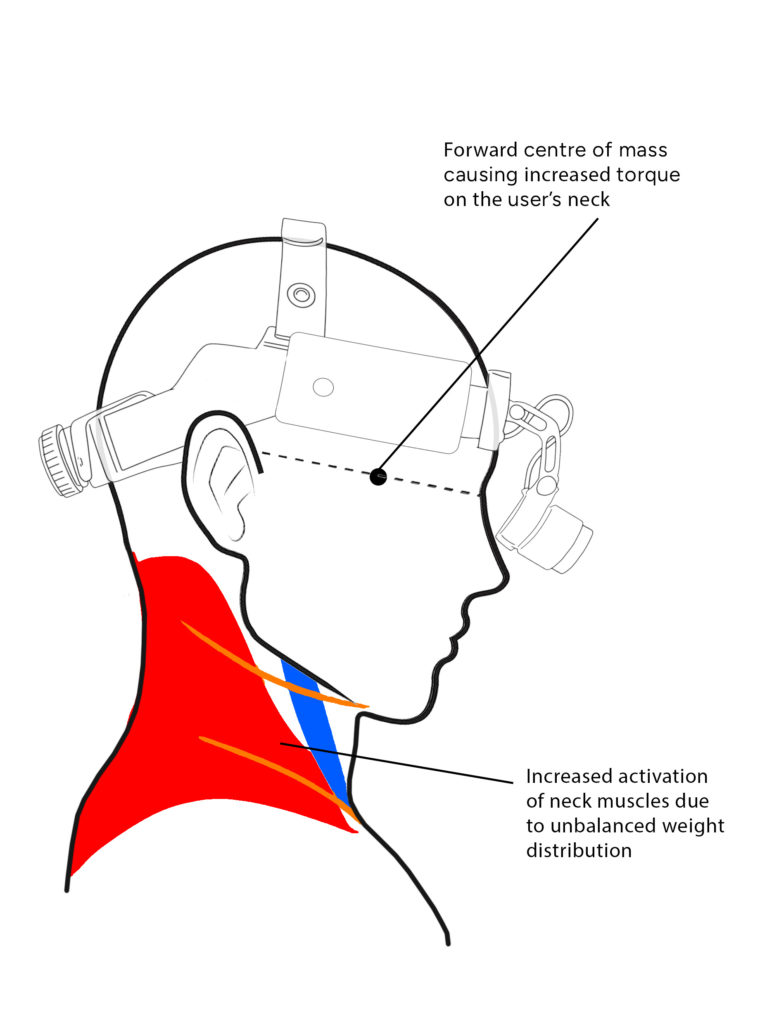

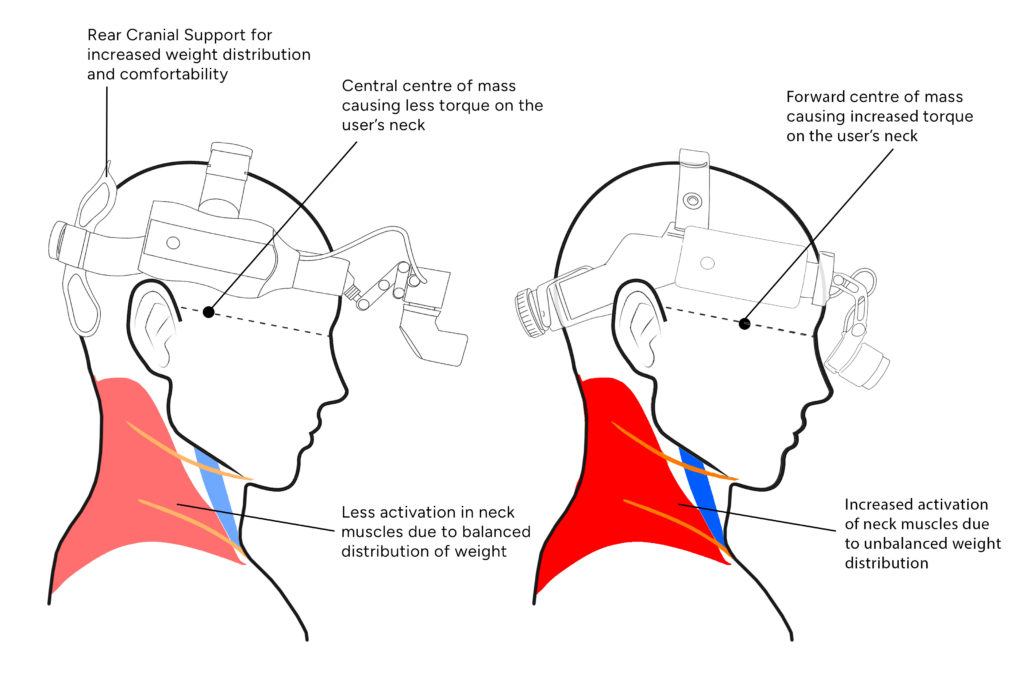

The weight and weight distribution of surgical headlights play a critical role in surgeon fatigue⁴. A forward or elevated centre of mass increases the moment arm around the upper neck joint, therefore requiring greater counter-torque and greater activation of the stabilising muscles in the back of the neck to maintain head stability. Sustained muscle activation over prolonged procedures has been associated with decreased fine motor control, discomfort and potential risk of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. These findings are consistent with research on other head-worn devices, suggesting that surgical headlights should be considered from an ergonomic perspective rather than a solely functional one.

Studies have shown that the centre of mass can be as influential as weight, as devices with a heavier forward centre of mass produce faster fatigue and greater discomfort⁴. Design solutions such as relocating the battery off of the head, counterbalancing the weight or using wide padded headbands to distribute pressure more evenly can significantly reduce muscle strain and improve comfort over longer procedures.

Brightness & Light Output

The brightness and light output of surgical headlights also have a direct influence on surgeon fatigue⁵. Excessive brightness or glare increases visual workload, causing the eyes to repeatedly adapt to differing luminance levels, which can subtly increase cognitive strain without being consciously perceived. Over time, this can contribute to visual discomfort, reduced depth perception, and a gradual decline in visual acuity⁵. When lighting conditions are inconsistent or poorly directed, surgeons may compensate by altering their posture to optimise visibility, which further increases muscular activation in the neck and upper back. To diminish these obstacles, adjustable light settings, flicker-free light output and homogeneous light distribution have been shown to reduce visual fatigue, highlighting the importance of lighting design as a factor in both surgeon comfort and procedural safety⁶.

Mobility

A key factor in surgical headlight design is mobility. The ability to move freely without resistance, constraint or anticipation of interference directly impacts a surgeon’s physical comfort, posture and endurance during procedures, all factors which influence fatigue⁷. Any components which add drag or resist natural head and body movements- such as cables, weight and weight distribution- require micro-compensatory effort from the neck, shoulders and upper back⁷. Even low levels of resistance can lead to muscle activation, which accelerates fatigue over time. Limited mobility can often lead to adjustments during surgery, which requires physical correction of posture and stance, disrupting procedural flow and increasing task duration and muscle fatigue⁷.

To address mobility-related fatigue, surgical headlight design should focus on preserving natural movement by minimising resistance through the use of lightweight, flexible materials, increasing adaptability by integrating modular systems to allow surgeons to personalise fit and to facilitate procedural flow by ensuring that devices can be adjusted single-handedly and without interrupting workflow. By prioritising these factors, musculoskeletal strain and cognitive fatigue are significantly reduced and contribute to surgeon comfort and long-term health¹.

The Solution

When ergonomic design factors- weight & weight distribution, brightness & light output and mobility- are prioritised, surgical headlights can contribute to reducing the risk of surgeon fatigue, musculoskeletal strain, visual stress and cognitive load.

When we apply these principles to the two surgical headlights in the Uniplex range, it becomes clear how design choices help to mitigate the risk of fatigue-related issues discussed above.

The LX2 is a wired, battery-powered surgical headlight, which means that the user is free from being tethered to a light source, promoting increased mobility and allowing for natural movements, reducing micro-compensatory muscular activation in the neck and upper back. Along with this, the lightweight 265-gram headband and rear cranial support reduce the load on the neck and distribute the weight of the headlight evenly, minimising the forward shift of its centre of mass, providing improved comfort and stability. Featuring a high-quality, bright white light, with a colour temperature of 5700°K, the LX2 provides an adjustable homogeneous spot of light, which can contribute to reducing strain on the eyes of the surgeon and less compensatory adjustments in posture over time.

Unlike the LX2, the SSL-5500 is a wireless surgical headlight, which means that the user is fully free from wires, eliminating resistance from cables, enabling surgeons to adopt more ergonomic postures throughout procedures, reducing micro-compensatory strain and cumulative musculoskeletal load. Due to being wireless, the battery of the SSL-5500 is located on the headband, bringing the total weight of the headlight to 420 grams; however, the placement of the battery has been carefully considered in order to preserve the centre of mass and avoid forward shift. The SSL-5500 also features a rear cranial support, which provides an even distribution of weight around the head for increased comfort and reduced load on the neck. With a colour temperature of 4500°K, the SSL-5500 provides an adjustable homogeneous spot of light, contributing to reduced strain on the eyes of the surgeon and less compensatory adjustments in posture over time.

Key Takeaways

The connection between design and fatigue is clear; poorly balanced or visually disruptive headlights increase muscular activation and cognitive load, influencing how quickly fatigue develops. When these elements are considered in design, fatigue is slowed, performance is sustained, and surgical outcomes are strengthened. Here are some of the key takeaways of the discussion:

- A balanced centre of mass creates a lower requirement for counter-torque, therefore reducing the risk of neck muscle strain and musculoskeletal disorders

- Flicker-free light output and homogeneous light distribution can help to reduce the risk of visual fatigue by ensuring consistent lighting, meaning that the eyes don’t need to constantly adapt to differing luminance levels

- Reducing the number of components which add drag or resist natural head or body movements can contribute to the reduction of micro-compensatory effort from the neck, shoulders and upper back, decreasing the risk of muscle fatigue

If you would like to learn more about our Surgical Headlights or arrange a trial, get in touch with us at Uniplex.

Click Here for more information on our Surgical Headlights

Click Here to get in touch or call 0114 241 3410 to contact us

References

1) Meltzer AJ, Hallbeck MS, Morrow MM, et al. Measuring Ergonomic Risk in Operating Surgeons by Using Wearable Technology. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(5):444–446. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2019.6384 – Click Here

2)Kumar H, Dhali A, Biswas J, Dhali GK. Reducing Surgeon Fatigue Through Ergonomics: Importance and Benefits in Laparoscopic Surgeries. Cureus. 2024 Jul 27;16(7):e65530. doi: 10.7759/cureus.65530. PMID: 39188426; PMCID: PMC11346823. – Click Here

3)Stucky CH, Cromwell KD, Voss RK, Chiang YJ, Woodman K, Lee JE, Cormier JN. Surgeon symptoms, strain, and selections: Systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical ergonomics. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2018 Jan 9;27:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2017.12.013. PMID: 29511535; PMCID: PMC5832650. – Click Here

4)Ito K, Tada M, Ujike H, Hyodo K. Effects of the Weight and Balance of Head-Mounted Displays on Physical Load. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(15):6802. – Click Here

5)Curlin J, Herman CK. Current State of Surgical Lighting. Surg J (N Y). 2020 Jun 19;6(2):e87-e97. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710529. PMID: 32577527; PMCID: PMC7305019. – Click Here

6)Yoshimoto S, Garcia J, Jiang F, Wilkins AJ, Takeuchi T, Webster MA. Visual discomfort and flicker. Vision Res. 2017 Sep;138:18-28. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2017.05.015. Epub 2017 Jul 21. PMID: 28709920; PMCID: PMC5703225. – Click Here

7)Toffola ED, Rodigari A, Di Natali G, Ferrari S, Mazzacane B. Postura e affaticamento dei chirurghi in sala operatoria [Posture and fatigue among surgeons in the operating room]. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2009 Oct-Dec;31(4):414-8. Italian. PMID: 20225645. – Click Here